Service User Involvement in the Regulation of Social Welfare Services: A Conceptual Framework

הוצג ע”י הילה דולב בכנס 7th Biennial Conference of the ECPR Standing Group on Regulatory Governance

Table of Contents

Abstract

Introduction

Definitions

Main Aspects of User Involvement in Welfare Services

SUI in the Regulatory Tasks

Conclusions

References

Abstract

The concept of service user involvement is relatively new in the literature of regulation in social welfare services. This concept is significant both conceptually and practically. Conceptually – it falls in line with a major challenge, which many countries face in recent decades, of safeguarding public values and interests and especially the well-being of vulnerable populations, following the shift from direct provision of social welfare services by the state to various non-governmental organizations. Practically, applying service user-involvement in the regulatory context has a potential impact on the quality of care provided by the services.

In my presentation, I will introduce a conceptual framework of user involvement in the regulation of welfare services. I will first examine the main themes and issues raised in the literature of service user involvement in welfare services – both on the individual level and on the service or national level. Based on these, I will suggest an analysis of service user involvement in the unique context of regulation of welfare services and regarding the three main tasks of: standard setting, monitoring and enforcement.

For each of these tasks, I will explore the essence and the significance of involvement, addressing the following issues: Why is involvement important? What are the potential benefits? What are the potential barriers? Above all: how can we know if the user involvement is meaningful or just for the sake of appearances? This suggests an assessment of the quality of involvement.

This framework is part of my PhD proposal. In my future research, I aim to explore user involvement in regulation, comparing different welfare services in Israel as well as in comparison to other countries. In this research, I aim to contribute to the development of an improved model of user involvement based on best practice.

Introduction

The main issue of my presentation is the interaction between the concepts of ”regulation” and “service user involvement” in the context of welfare services. While both concepts have taken a significant place over the years in the public and social policy literature, the discussion about the interaction between them seems to be relatively rare.

During the last three decades, the provision of welfare services in Israel, as in many other countries has been going through rapid changes that reflect changes in social policy. These include more privatization and outsourcing of services, followed by an essential change in the role of the state – from providing services to enabling them. A new challenge arose as to safeguarding public interests, especially with regard to vulnerable populations, which led many countries to rethink and reshape their regulatory policy. It is often argued that, in Israel, the vast growth of privatization was not followed by sufficient investment in regulatory policy and practice, creating a “regulatory deficit” (Levi-Faur, 2014).

Parallel to these changes, there has been a growing focus on service user involvement, considering it as an important aspect of enhancing democracy as well as a solution to problems concerning the delivery of welfare services (such as abuse or other care failures). This reflected a shift in policy from paternalistic models of welfare care to user-centered models that emphasize human rights and open up the domain of knowledge, previously seen as exclusively related to professionals (Birrel et al. 2017).

Interestingly, the literature on regulation and on service user involvement (SUI) apprise similar new trends, both concerning the decentralization of the state. As regard to regulation, there is a growing trend of strategies that are no longer state-centered, such as meta-regulation, smart regulation and even self-regulation and voluntarism. Black has gone further to announce the term “regulatory society” which implies that regulation is no longer centered on the state, but has rather been diffused throughout society (Black, 2017). As for SUI, trends has gone beyond involvement in the delivery of existing services to a more active involvement in the provision of services and in policy formulation (Croft and Beresford, 1996).

In the reality of welfare services in many countries, these trends are not yet widespread and at least parts of the regulation tasks (standard setting, monitoring and enforcement) are still state-centered or at least external to the provision of care (e.g. run by local authorities). In these circumstances, as I will demonstrate later, SUI has clear rationale and potential benefits, but it is not without challenges. Hence, I suggest that it is not enough to track whether involvement exists but also to assess its quality.

Definitions

Both “Regulation” and “Service user involvement” are concepts that are defined in wide and varied ways related to different types of contexts. Before proceeding, I will relate to the specific definitions I adopt for my analysis.

“Service user involvement”

I chose to adopt Julkunen & Heikkila’s definition for user involvement (2007): “In the context of welfare services, user involvement is often perceived as the possibilities of users to affect the content and quality of public services” (Julkunen & Heikkila, 2007). This definition suits my analysis for several reasons. Firstly, it implies that the involvement has an impact, as opposed to situations in which people only take part or participate in activities. Secondly, it goes beyond the individual level (one’s own care) to encompass involvement in the service or even on the national level, concerning the design and delivery of services. Finally, it aligns with the essence of regulation, which is also a mechanism of intervention, aiming at affecting the provision of care.

“Regulation”

Bundred and Grace (2008), in relating to external and quality regulation of public services, define regulation as “…activities aimed at improving services, reporting on their performance and providing assurance that minimum standards are being met. It also includes a wide range of other activities that might be described as economic or ‘market regulation’…focused on promoting competition and protecting consumers against monopoly power” (Bundred and Grace, 2008 p.103). This definition includes the function of regulation as safeguarding individual interests both at the service level (ensuring minimum standards) and at the market level (monopoly power). In addition, it implies the effect on quality of care (improving services, promoting competition). Finally, it also implies the main tasks of regulation – as Baldwin et al. (1998) have defined: standard setting, monitoring and enforcement.

Thus it is reasonable to assume that, in the context of welfare care, “Regulation” and “involving service users” correlate by definition as both are mechanisms that aim to affect the quality of care.

Main aspects of user involvement in welfare services

The Consumerist vs. the Democratic approach

There are two main lenses recognized in the literature through which SUI in welfare services can be analyzed. One is the consumerist approach, which refers to welfare services as commodities that can be bought or sold, emphasizing market principles such as efficiency and improved management. In this sense, service users are expected to be able to choose a service that is best for them and to leave a service whenever they feel that it does not meet their expectations or, alternatively, when they feel their problem has been solved. This approach implies the importance of creating opportunities and access for service users’ choice.

In contrast, the democratic approach emphasizes human rights and equality of opportunities. It refers to service users as active citizens, able to articulate and negotiate their needs and expectations whilst still using the service. This approach implies the importance of creating opportunities and access for service users’ voice.

While users’ choice is an economic concept by essence, users’ voice is a political one (Healy 2017). Barnes (1999) in her work “Users as Citizens”, sharpens this distinction. By addressing the term ‘citizenship’, she draws attention to two different user’s identities: “citizen” and “consumer”. Hence, as she states: “Collective action based in common experiences of oppression, disadvantage or social exclusion should be distinguished from an assertive consumerism which seeks to maximize individual self-interest” (Barnes 1999).

As regulation mechanisms affect the provision of welfare services, it is useful to consider both approaches when analyzing the essence of service user involvement in regulatory tasks.

Benefits of service user involvement

Various prominent benefits are linked with service user involvement in the provision of social services. These can be categorized as moral/ideological, psychological or individual, social, and practical. The Moral/ideological benefits consider involvement as reflecting a vibrant democratic society and the practice of human rights. The psychological – individual refers to empowering service users, strengthening their independence, self-esteem and self-efficacy, all of which are essential to improve quality of life especially for those who receive welfare care. The social benefits refer to creating an equal relationship between users and professionals and a better relationship between users and the government. In addition, involvement can potentially create solidarity within groups and communities.

Finally, the practical benefits refer to the ways users’ involvement can affect the quality of care. These relate to the unique features of welfare services where the consumption and the production of a service are inseparable. Because the care typically involves a high level of intimacy, both the provider and the user influence the quality of care and service users are actually co-producers of their own care (See Malley et. al 2010).

Although these benefits are related to involvement in the provision of welfare services, they can also apply to the context of regulation. Involving service users in regulatory tasks embeds potential moral, psychological and social benefits. Moreover, from the practical aspect I suggest that user involvement is crucial to each of the regulatory tasks, standard setting, monitoring and enforcement, as I will demonstrate later.

Barriers to SUI

Although there is a consensus that involving users is important, there are also recognized barriers. These can be categorized as structural and interpersonal relationships. The structural include the lack of information, opportunities, access and legislation that supports SUI. In the regulation context, barriers of this type could be lack of policy initiatives that regard SUI as a duty in the regulatory tasks.

Other barriers relate to relationships. From the service users’ perspective, being active and involved can raise concerns and fears as it implies a greater responsibility of the user on the care provision. Users might also lack the necessary skills needed to articulate and negotiate their needs. From the professional perspective, it implies a reduced level of control. In the regulation context, the relationship between regulators and service users could be challenging. As regulators are not part of the service staff, their interaction with service users is relatively rare, implying a low level of acquaintance. This can lead to low level of trust, communication gaps, and a fear to raise concerns or make complains about a care on which one is highly dependent. All could be potential barriers to collaboration between service users and regulators.

Assessing the quality of user involvement

One of the main issues concerning SUI is its meaningfulness. Since there are inherent challenges in SUI, then once practiced, it is necessary to ask: how meaningful the involvement really is? This relates to assessing the quality of involvement. Various researchers have described involvement misuse, implying that occasionally, there are good intentions but bad implementation or even worse, sometimes there are bad intentions and manipulation, which means using SUI for the wrong purposes (Arnstein, 1969; Beresford et al 1996; Levin, 2012). In these circumstances, the involvement is not effective and does not enable real voice or choice.

Two examples of misuse of SUI are involvement used in order to either delay/procrastinate actions (e.g. ad hoc consultations), or to legitimize pre-determined decisions or specific providers/professional interests such as public relations (Beresford et al 1996).

Braithwaite et al. (2007) have mapped different forms of ritualism concerning regulation. They argue that regulators often fall into behaviors, which give the appearance of striving for improvement without really bringing about substantive change. This stems from a variety of reasons, one of which is the will of politicians to deregulate on the one hand whilst the public demands for increased regulation on the other hand. One of these forms of ritualism is ritual participation, which they describe as the instances in which “[regulators] follow procedures that pretend to enhance participation, but instead alienate (or put to sleep) supposed participants” (Braithwaite et al, 2007 p.221)

Looking into the cases illustrated in the literature of meaningful or alternatively ritual involvement, exposes three dimensions for assessing the quality of involvement. One dimension can be defined as power and control. This relates to the extent to which the service user receives real power in order to pursue a relationship based on equality. Two factors come in to play here: the scope and the timing of the decisions, and the nature of the relationship between the service user and the service professional or the regulator. For example, when service users are involved from early on in the process there is a good chance that their voice will be heard and have a genuine impact, as opposed to involvement after decisions have been made. Another example of ‘real’ user involvement is when the process is of a collaborative nature, meaning service users and service professionals make shared decisions which are based on their shared knowledge and experience (Levin 2012).

Another dimension in assessing the quality of involvement is representativeness, which relates to the extent to which the people involved represent the broader user population. The literature points out that there is a tendency to marginalize groups of users due to various differences such as race, gender, age, disabilities and even communication gaps. A genuine and meaningful involvement encompasses every kind of user including those who are more difficult to reach and are typically marginalized.

The third dimension relates to the involvement impact, regarding the extent to which the service users’ input has a direct impact on decisions and change. The literature points out the phenomenon of ‘consultation fatigue’, when individuals hesitate or even avoid being involved just because they feel that too frequently their input is not taken seriously and does not promote change (Croft et al. 1996).

SUI in the regulatory tasks

In this section, I analyze the nature of involvement in each of the three main tasks of regulation: standard setting, monitoring and enforcement. The issues addressed here are: what is the significance of involvement? What are the challenges? And how could we assess the quality of involvement?

Standard Setting

Standard setting is about shaping policy. It sets the goals and defines the values by which the services should function when providing care. Hence it implies that wherever there is a real aspiration to form user-centered and responsive services, that recognize users’ needs and rights and strive to meet them, it is crucial that service users will take part in this process.

SUI in standard setting should relate to the process of decision-making. Practically, it requires collaboration based on a dialogue between the regulators and the users, in which all actors articulate their knowledge and experience, needs and expectations, and choose between options. Mostly, it requires a collective action enhancing users’ voice.

Potential barriers for this process could be of a structural type – lack of opportunities for involvement because of relatively rare situations in which standards are being set or updated or lack of structured procedures of involvement. Barriers could also be related to the kind of relationship between the regulators and the service users. As regulators are external to the service, lack of acquaintance, lack of skills or communication gaps, can challenge the level of collaboration.

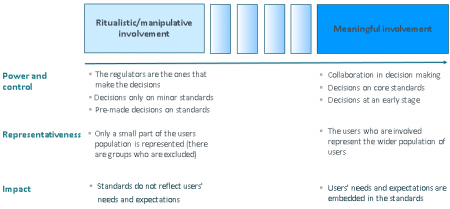

As SUI takes place, it is useful to assess its quality. Figure 1 presents a continuum of the quality of SUI in standard setting based on the three dimensions mentioned earlier – power and control, representativeness, and impact – with suggested indicators for assessment.

Figure 1: Quality assessment of SUI in standard setting

Monitoring

Monitoring is about examining the ways in which services function, as related to the requested standards. It requires ongoing actions of observing and tracking both the strengths of the service, that is compliance and continuous improvement, and the weaknesses, namely non-compliance or even violations, which could potentially carry a danger.

Similar to the task of standard setting, SUI in standard monitoring requires an enabled user’s voice, which in this case means, users who are able to track and provide feedback (optimally ongoing) on the quality of care, in relation to their rights embedded in the standards. As much as regulators have information about what is going on, even with the most sophisticated procedures of data collection, they cannot really have the whole picture without involving service users who actually experience the care. In this sense, service users’ voice serve as a crucial source of information for the regulators.

Potential barriers for this process could be of a structural type – lack of opportunities or channels for providing feedback, lack of access and lack of information about the standards. Concerning relationships, users could have concerns in raising negative feedback or making complaints, fearing it would put their relationships with the service staff at stake, resulting in worse care.

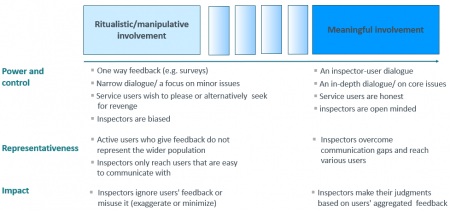

Figure 2 presents a continuum of the quality of SUI in standard monitoring, based on the three dimensions mentioned earlier, with suggested indicators for assessment.

Figure 2: Quality assessment of service user involvement in monitoring

Enforcement

This task is about making judgments about the quality of care as related to the expected standards and goals, and taking actions (e.g. performance scores, licensing, incentives and sanctions). SUI here has two different rationales: one is in driving improvement of the specific service in which the user receives care and the other is in affecting the market.

The service users’ role here, could take two different directions, one relates to voice and one to choice. One direction is service users taking part in the decision making process on the judgements and the actions that need to be taken. Similarly to the task of standard setting, this kind of involvement concerns enabling service users’ voice and inheres similar challenges. Yet, a unique significance here is giving users the power to affect the market: performance scores, as well as other enforcement actions, have a clear effect on both the purchasers (choosing to keep funding a specific service or alternatively, favor a different one) and on users (who can choose to stay or leave a service).

So SUI in the enforcement task combines both users’ voice, in the democratic sense, and users’ choice in the economic and the individual sense. Figure 3 presents a continuum of the quality of SUI in enforcement, as it refers to voice and choice.

Figure 3: Quality assessment of service user involvement in enforcement

Conclusions

In my analysis, I tried to shed light on the significance of SUI in the context of welfare services regulation. It has already been recognized that SUI has clear benefits as a mean to achieve outcomes on the individual level (e.g. empowered, independent and self-confident individuals) and on the service level (e.g. improved, responsive and person-centered care). It has also been recognized to be of value as a mean by itself – serving to strengthen the democratic society and enacting human rights. But it is also quite clear that when SUI is practiced, it is necessary not only to celebrate its existence, but also to examine its quality. The model that I suggest can serve not only for such an assessment but also as a framework for designing SUI policy and practice. This model needs to be validated in an empirical research.

References

Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216-224.

Baldwin, R., Scott, C., & Hood, C. (1998). A reader on regulation Oxford University Press.

Barnes, M. (1999). Users as citizens: Collective action and the local governance of welfare. Social Policy & Administration, 33(1), 73-90.

Birrell, D., & Gray, A. M. (2017). Delivering social welfare: Governance and service provision in the UK Policy Press.

Black, J. (2017). Critical reflections on regulation. Crime and regulation (pp. 15-49) Routledge.

Braithwaite, J., Makkai, T., & Braithwaite, V. A. (2007). Regulating aged care: Ritualism and the new pyramid Edward Elgar Publishing.

Bundred S, & Grace C. (2008) Holistic Public Services Inspection in Davis, H., & Martin, S. (Eds.). Public services inspection in the UK Jessica Kingsley Publishers. pp 102-119

Croft, S., & Beresford, P. (1992). The politics of participation. Critical Social Policy, 12(35), 20-44.

Healy, J. (2017). Patients as regulatory actors in their own health care. Regulatory Theory, 591-609.

Julkunen, I., & Heikkilä, M. (2007). User involvement in personal social services. Making it Personal.Individualising Activation Services in the EU, , 87-103.

Levi-Faur, D. (2014). The welfare state: A regulatory perspective. Public Administration, 92(3), 599-614.

Levin, L. (2012). Towards a revised definition of client collaboration: The knowledge–power–politics triad. Journal of Social Work Practice, 26(2), 181-195.

Malley, Juliette and Fernández, José-Luis (2010) Measuring quality in social care services: theory and practice. Annals of public and cooperative economics, 81 (4). pp. 559-582.